The case of The Owners of the Vessel Sakizaya Kalon v The Owners of the Vessel Panamax Alexander [2020] EWHC 2604 (Admlty) concerned a dispute arising after a collision that occurred between three bulk carriers in the Suez Canal. The claims arising totalled some USD 18 million. Andrew Shannon and Joehunt Jinnah of the CJC Singapore office provide the summary.

The Owners of the Vessel Sakizaya Kalon v The Owners of the Vessel Panamax Alexander [2020] EWHC 2604 (Admlty) was the final case heard by Sir Nigel John Martin Teare before his retirement as an Admiralty Judge this year. The case itself involved a consolidated action for a collision involving three bulk carriers transiting the Suez Canal. It is a stark reminder of the importance of common sense when navigating and of the utmost importance to maintain a good lookout by all available means.

Broadly, the case concerned a dispute arising after a collision that occurred between three bulk carriers in the Suez Canal. The claims arising totalled some USD 18 million. The judge held that the rearmost vessel in the convoy, Panamax Alexander, was wholly to blame for the collision for failing to moor in time.

Facts

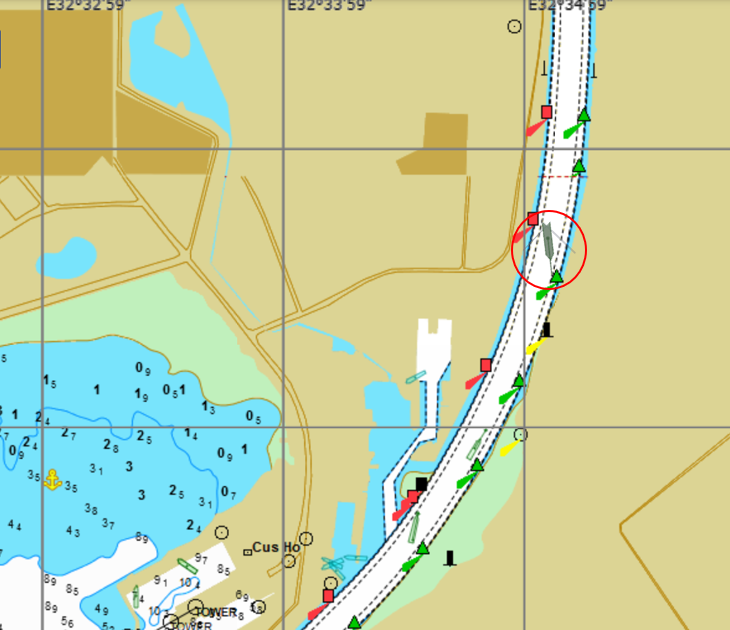

At about 17:50, the container vessel Aeneas, (who was at the head of the convoy), suffered an engine problem and was forced to anchor. She was finally anchored by around 18:20, and at the time she was almost at the termination of the Suez, by Port Tawfiq, please see figure 1 below:

Figure 1

The effect of this was that the Suez Canal became blocked and forced other vessels who were further north to take steps to either moor or anchor. The majority of vessels achieved this, but not all were successful.

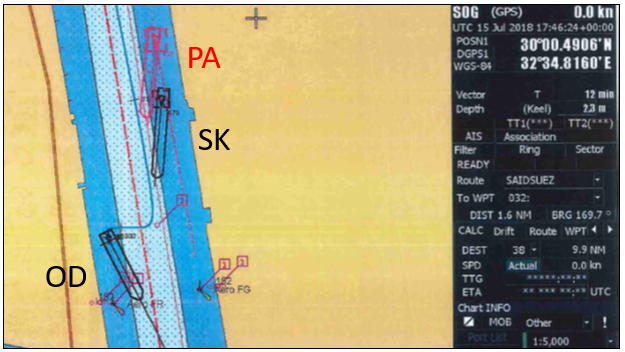

At about 19:48, Panamax Alexander (“PA”), who was the eighth (and last) vessel in the convoy, collided with Sakizaya Kalon (“SK”), the seventh vessel in the convoy, see figure 2 below[1]:

Figure 2 - 19:46LT – PA very shortly before first contact with SK

At the time of the collision, SK was either at anchor or moored up (there is dispute as to her status) alongside the eastern bank of the Suez Canal. Ahead of SK was another vessel, Osios David (“OD”), who was also anchored but moored to the western bank of the Suez Canal.

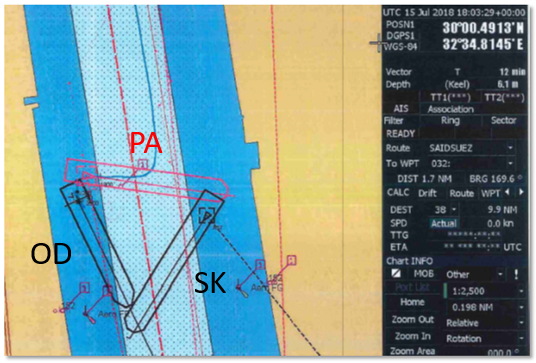

Upon the first collision between PA and SK, the two vessels shifted forward and at about 20:02, also collided with OD. The vessels ended up in a remarkable triangular shaped position and made further contacts with each other until they separated, please see figure 3 below[2]. The final contact was between PA and SK.

Figure 3 - 20:03LT - The later collisions

OD sued PA in one action and SK in another action. In a third action, SK sued PA. PA counterclaimed against OD and SK. The actions were heard together.

The collisions occurred between the stretch of the canal marked KM 151 and KM 153. It is common ground that between KM 149 and KM 151 laid submarine cables and pipelines which impeded a vessel’s autonomy to utilise her anchors to assist in mooring.

OD and SK argued that PA failed to moor before KM 149 and thus, could not use her anchors to assist in mooring leading to the collision. PA argued, inter alia, that OD and SK failed to inform PA of their intentions to moor and created a dangerous situation by obstructing the passage in an area only a cable’s length in width.

Analysis/Judgment

Mr Justice Teare found that PA had failed to comply with her obligations under the Collision Regulations (COLREGS), in particular, Rules 5 (duty to keep a good lookout), 7 (duty to determine if a risk of collision exists) and 8 (duty to take such action as required by good seamanship in a particular circumstance).

The judge found that it was PA’s failure to recognise a risk of collision and her resultant failure to moor before KM 149 (i.e. before submarine cables/pipelines) that was causative of the collision between PA and SK. Furthermore, Teare J noted that after failing to moor before the appropriate zone as a prudent master would, PA also failed to drop her anchors in time when she could, and this contributed to the collision between PA and SK.

PA’s contentions that OD and SK were to blame as they failed to, inter alia, advise PA of their intention to moor was rejected by the judge. Whilst finding that OD was indeed at fault for failing to notify the vessel directly astern (SK) of her intention to moor, the judge found that this was not causative of the collisions.

In any event, PA could not show that she would have reacted differently even if such notice were given by OD or SK. Indeed the judge noted that PA did not take action to moor even though she was informed earlier that there was no longer any movement up or down the canal because of AENEAS or when observation by ECDIS and AIS suggested that the five vessels further down the convoy were about to moor.

The judge stated that common sense would dictate that PA ought to have prepared mooring in such instances. For these reasons, Teare J held that it was more likely that PA had failed to appraise the situation and the risk of a collision, a failure of COLREG rule 5.

The judge concluded that the collision between PA and SK was caused wholly by the fault of PA in her failure to moor in the appropriate stretch of the canal (namely before KM 149). In addition, the judge stated that the first collision, “…not merely provided the opportunity for the later collisions but constituted the cause of them”[3].

Comments

It is fairly unusual for a judgment to find a vessel wholly to blame for a collision. It is even more unusual for such a finding when multiple vessels are involved, making this case somewhat unique.

As mentioned, this collision emphasises the importance of maintaining a good lookout and to apply common sense. Although not alluded to in the judgment, Rule 2 of the COLREGS already provides for such common sense and is often a rule that is overlooked. Broadly, the first part of this rule requires one to follow both the rules and "the ordinary practice of seaman". This rule calls for those to follow all the normal and accepted practices that one would expect to find at sea, or to put it another way, to use common sense. It is encouraging to see more emphasis placed on common sense in this judgment.

The case also highlights the importance of preserving records especially with regards to VDR, ECDIS and AIS. A great amount of emphasis was placed on the VDR transcript at trial and in many instances, the judge found that some evidence given could not be corroborated by the VDR when they ought to have been. Indeed, the VDR was scrutinised so much so that at one point, Teare J stated that the Master of PA had fabricated evidence to evince why PA did not moor when it should have[4].

Before the time of VDR, ECDIS and AIS, the shape of a collision action in the Admiralty Court was to work out how and where the collision had occurred and from this, judges could establish and apportion liability accordingly. Before electronic evidence, when each of the parties’ collision statement of case (formerly known as the Preliminary Act ), were taken and plotted out, one would usually find that it was not possible to get the ships to collide with one another. It was only through the use of forensic analysis of the navigation, ship handling, working charts and other such contemporaneous evidence, that experts could unravel influences that had been made to the evidence in an attempt to establish the cause of the collision.

As this case illustrates, these days parties arrive at trial with the navigation of the vessels agreed in very considerable detail, the focus now being, “questions of fault (whether a vessel failed to comply with one or more of the Collision Regulations or the requirements of good seamanship) and questions of apportionment of liability (which requires assessment of the causative potency of a vessel’s fault and the degree of blameworthiness of such fault)”[5].

In Teare J’s closing paragraphs, he thanked counsels and those instructing him, as they made this, his last case as the Admiralty Judge, a pleasure to decide.